Twenty-five years may have passed, but Raewyn Wallace remembers the night she learned her son had been shot dead by New Zealand police as if it happened yesterday.

“We were just sitting by the fire and we were talking about the rugby was on, and so I said, look, I’ve been working, I’ve got to go to bed, I’m tired. So we went to bed.

“In the middle of the night, I got up and he’d gone out; that was nothing new. And I never saw him again,” she said.

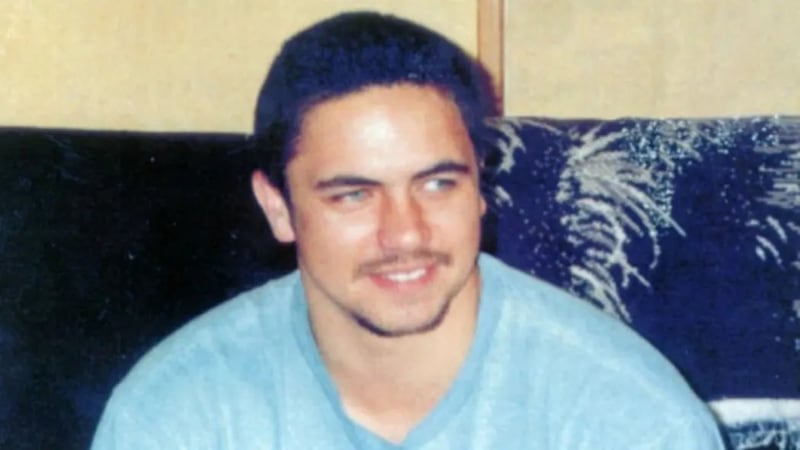

Steven Wallace was 23 years old when, in the early hours of 30 April 2000, police shot and killed him in the small Taranaki town of Waitara.

Officers claimed he had been smashing shop windows with a golf club.

According to a police report, Steven died from an unsurvivable gunshot wound to the liver. It stated that no action or inaction—by anyone could have saved him.

But for Raewyn, the explanation has never been enough. She’s spent the past quarter-century demanding accountability.

“He was going to be an architect, and he was, you know, such a good drawer, and he was so good at it,” she said.

“He was always going to build this big house and, you know, we should be living in this big house with all his kids and whatever, and he missed out on all that.”

Ka whawhai tonu te whānau

The family’s fight for justice has been long and exhausting.

In 2001, the officer who shot Steven—Constable Keith Abbott—was charged with murder, but later acquitted.

Raewyn said she was shocked to discover the government had paid for Abbott’s legal defence.

“I had to go and find $75,000 just to get there,” she said.

“And so everything that we’ve done, even to try and get an inquest at the beginning, we were told no.

“When we went to court to get an inquest at the beginning, Susan Hughes said no, because if we go and have a trial against the police officers, they could purge it themselves and the Wallaces could sue a large amount of money for failing to provide the necessities of life to Stephen,” she said.

Now in her seventies, Raewyn has taken her case to the United Nations, accusing New Zealand’s legal system of failing her son and her whānau.

She says she will continue fighting for justice until her last breath.

“Well, he wasn’t this real horrible person, that’s for sure. You could ask anybody. Stephen used to help his friends at school,” she said.

“He used to tell the kids, Don’t go to school to mess the teachers up. You go to school to learn. They’re not there for that. This was his motto. You go there, and if you want to learn, you’ll go there. If you don’t want to learn, don’t go.”

Raewyn is now working on a book, due to be published later this year, which she hopes will empower other families who have experienced what she calls mistreatment by police.

For her, telling her story is about more than her son—it’s about changing a system.