Lepcha language students at Modern Senior Secondary School in Gangtok, Sikkim

Video journalist Rituraj Sapkota is travelling in South Asia and writing about conservation, sustainability and indigenous practices. In Sikkim (India), he describes how the success story of the Róng/Lepcha language was shaped by state policy.

“The Lepcha language has flourished in Sikkim,” says Ren (kaumatua) Karma Loday Lepcha of the Sikkim Lepcha Literary Association. “All because it was declared an official language in 1977.”

Sikkim is a state in Northeast India. Nestled amidst the Himalayas and bordering Tibet, Nepal and Bhutan, it was an independent kingdom until 1975 when India annexed it, deposing the chogyal (king). The Lepcha (who call themselves Róng) are thought to be the earliest inhabitants of the region surrounding the Kanchenjunga, the world’s third-highest peak.

The Róng believe they were created from the snow of the Kanchenjunga and the peak is revered by Róng who are today spread across three countries - Nepal, Bhutan and India. In India, their numbers are the largest in Sikkim, where they make up close to 10% of the state’s population, and in the adjoining hills of West Bengal, most notably Kalimpong.

It is only in Sikkim that the language is taught formally in schools and universities.

“It's all because of the government's initiative. We wouldn’t be here without recognition in 1977,” says Ren Tom Tshering Lepcha of the Sikkim Lepcha Literary Association.

Ren Karma Loday Lepcha (left) and Ren Tom Tshering Lepcha (right) of the SIkkim Lepcha Literary Association. The word Ren is an honorific used for respected, elderly members of a community.

Róng, religion and politics

The role of the state is visible throughout history, Ren Tom Tshering says. The Róng script was developed in the 15th century. For most of recorded history after that, Sikkim was ruled by Bhutia kings. The Bhutia migrated from Tibet in waves and brought with them Buddhism and religious texts in Tibetan.

The third chogyal in the 17th century started commissioning the translation of Buddhist texts into the Róng language. In the following century, Scottish missionaries entered the kingdom. They learnt the language and translated the Bible into Róng-ring (the Róng language), to convert the Lepcha to Christianity. The missionaries were aided by the advent of printing presses in India, allowing them to mass produce their scriptures. Meanwhile, handwritten Buddhist texts and calligraphy continued. This rivalry benefited the language, Ren Tom Tshering says.

Sikkim on the map. It was one of the “buffer” Himalayan kingdoms alongside Nepal and Bhutan on the Indo-China border until 1975 when it merged with India

The invasion by the Gorkha kingdom (Nepal) and the arrival of Nepali-speaking people from the west in the years that followed changed the demographics of Sikkim. The kingdom had a complex relationship with British India, and by the time India became independent (1947), Nepali had become the most commonly used language in Sikkim while Bhutia was the official language.

After its merger with India, the newly formed Sikkim state declared Róng-ring as an official language. That was a game-changer.

Formal classes began in primary schools and, by 1984, students could opt to study Lepcha in year 12. Today, Sikkim University offers courses up to the masters level, and “PhD started last year,” Ren Tom Tshering says.

'The future is in safe hands'

“When I am walking the streets of Gangtok and pass 20 people, I hear two people speaking to each other in Lepcha,” he says. “And this is in the (capital) town which is very diverse. The language is thriving in the villages.”

“There are villages where people only talk Lepcha,” says Ongmit Lepcha, a Lepcha language teacher at Modern Senior Secondary School in Gangtok. “I have never heard my grandmother speak Nepali. She and others may watch TV in Hindi or English but they only talk to each other in Lepcha.”

Students in her Lepcha class don’t just learn the language, she says. “I also share with them folk tales and things I have learnt from observing my grandparents.”

The learning goes both ways. “I get to know many things from my students. They are from different places and each place comes with its own stories and folk tales and practices,” Ongmit says.

The Kalimpong connection

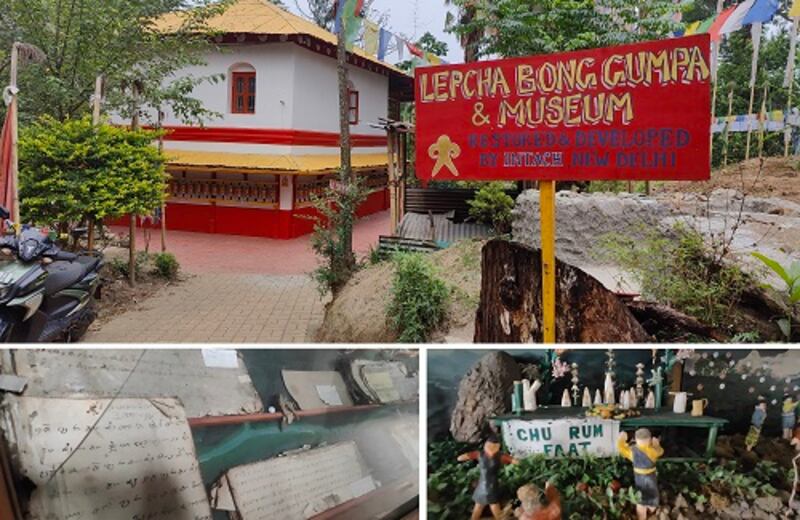

“In Sikkim, they were able to build a strong foundation. It is heartwarming to see,” says Karbong Lepcha of the Indigenous Lepcha Tribal Association, Kalimpong. Karbong runs the Lepcha Museum that displays the collection put together by his father, Sonam Tsering Lepcha.

“He wanted to make sure the Lepcha way of life doesn’t vanish,” he says.

Kalimpong was ceded to the British by Bhutan in 1865. After independence, it became a part of the Indian state of West Bengal.

Kalimpong was always a Lepcha stronghold, says Karbong. But Róng-ring is not an official language in the state. Formal education in schools hasn’t taken off.

The state government recently appointed close to 50 teachers to teach in primary schools but they were stopped from working by the Gorkha Territorial Administration, the semi-autonomous council that administers Darjeeling and Kalimpong, “perhaps because they saw it as overreach by the state government,” Karbong says. The trained teachers now run night schools in villages across Kalimpong district.

“When Sikkim was setting up Lepcha language courses, it was language experts from Kalimpong who helped design their curriculum. It hurts to see that we haven’t been able to do the same here at home,” says Karbong.

“Just like an oil lamp that gives out light to its surroundings but, right underneath it, there is darkness,” he says.

The Lepcha Museum in Kalimpong built by Karbong’s late father Sonam Tshering Lepcha showcases scriptures, artefacts and snippets of the Lepcha way of life.

Both in Sikkim and in Kalimpong, there is a movement to include Lepcha in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian constitution- the list of official languages of the country, Karbong says. There are 22 languages in the Eighth Schedule, with demand for another 39 to be included.

'We don’t have the numbers'

Across the international border in eastern Nepal, the Róng number about 3600. Here, the surname is spelt Lapcha, a variation dating back a few centuries. Bir Bahadur Lapcha, President of Róng Sejum Thi (Lapcha Upliftment Forum) says the small number works to their disadvantage. While the Constitution of Nepal, 2015 guarantees the right to education in one’s mother tongue, it rarely translates into practice.

“They have set up a Language Commission as well but it is in Kathmandu and its presence is not felt in our far-flung villages,” he says.

One rural municipality has started teaching Lapcha at the primary level, while another has declared a public holiday for Nambun, the Róng New Year.

“But there is only so much that a community can do,” he says. For a language to take off, textbooks have to be printed, a syllabus has to be prepared, and teachers need to be trained. None of this can be done without the express support of the state, Lapcha says.

“Just look at how they did it in Sikkim,” he says. “People who hadn’t formally studied the language were able to lobby and develop a curriculum, and as a result the language is thriving.”

Lapcha women in the Ilam district of Nepal. The word Ī-lam comes from Róng, says Bir Bahadur Lepcha, and means “where the ī (stingless bees) fly”

Migration and mixed marriages

But even the Sikkim model has its challenges. Intergenerational transmission in today’s world where indigenous languages have to compete with mainstream languages is tough, Tom Tshering Lepcha says.

Children, especially from affluent families, move to larger cities across India to study.

“I feel happy to see them expand their horizons,” he says. “But it also means that they will be communicating in Hindi or English there, and the connection to their language gets broken.”

Marriage between different communities is beautiful but it poses a challenge to language, says Ongmit Lepcha, who has noticed it among her students. Lepcha are increasingly marrying outside their community and the children struggle to learn the language if both parents don’t speak it at home.

Bir Bahadur Lapcha says the challenge is amplified in Nepal, where emigration is common. People who move out of their villages live in mixed groups and speak Nepali. The encroachment from mainstream society is not just in language. Hindu customs have replaced Róng customs in marriage, birth and death, he says.

Karbong Lepcha also acknowledges the influence of institutionalised religion. “Lepcha who have converted (to Christianity) are sometimes sceptical of participating in our biggest festivals, perhaps because they see these practices and prayers as pagan,” he says.

Modern Senior Secondary School where Ongmit Lepcha (in a grey coat, seventh from right)teaches conducts its morning assembly once a week in Róng-ring. It also has assemblies in Bhutia, Limboo, Nepali and English.

Ongmit, however, feels that the next generation is true to its roots.

“Not every Lepcha child in our school goes to Lepcha class. But the moment you talk of culture - whether it be a dance or conducting the assembly in Lepcha, you will see they are participating, they are wearing their traditional dress.”

As for her language students, many of them say they want to be Lepcha teachers. “And that makes me feel so proud,” she says, beaming.