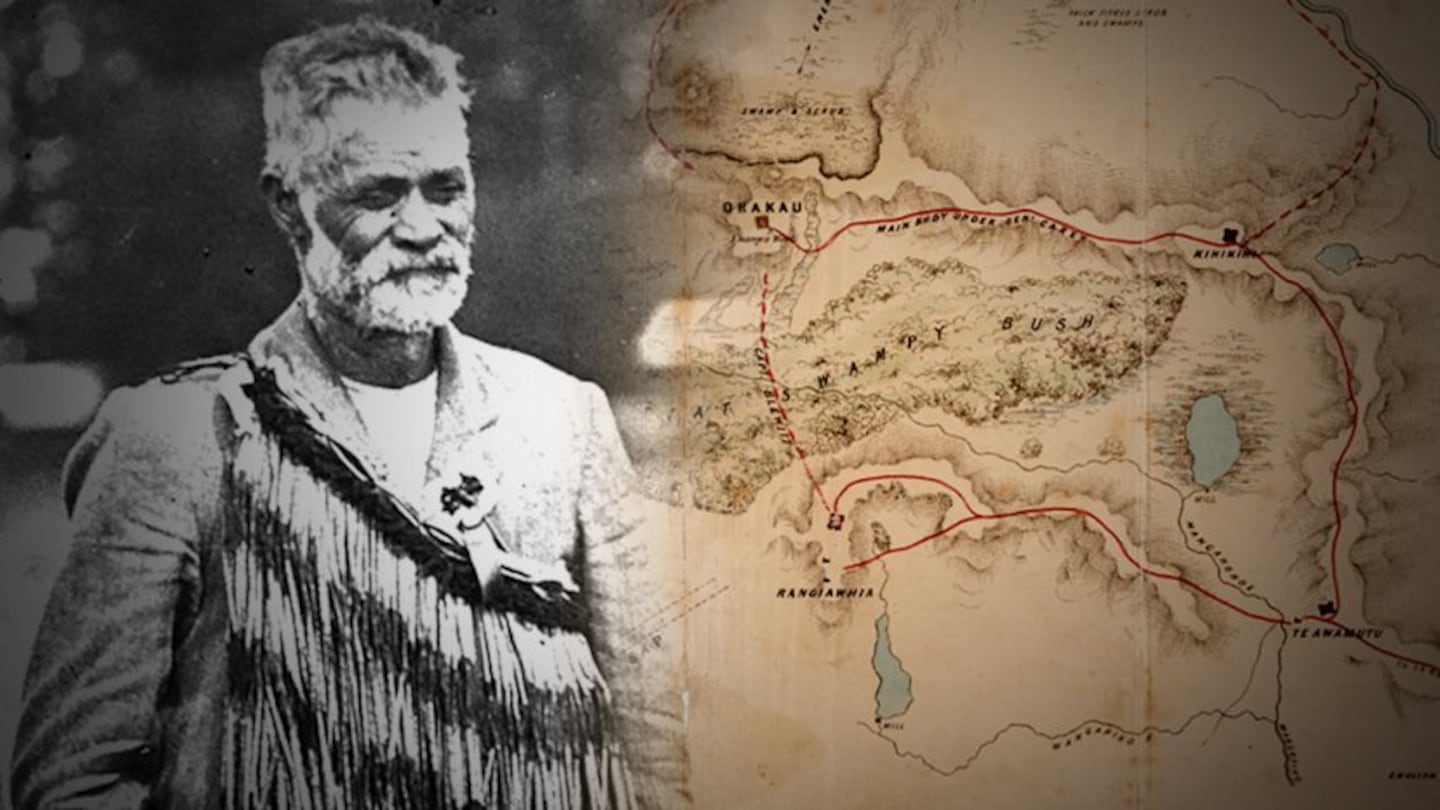

155 years ago marks the end of the March 1864 battle of Ōrākau, where 300 Māori fighters including men, women and children fought 1,100 members of a New Zealand government militia to prevent settlers from taking any more Māori land.

One of the legends from the battle of Ōrākau was Poupatatē pou o te rangi Huihi a.k.a. Thomas Hughes or Tāmati Huihi of Ngāti Unu, Ngāti Makohori, and a range of other hapū of Ngāti Maniapoto.

But who was Huihi? What did he do at the battle Ōrākau and why is he one of the 300 Māori remembered in histories of the battle?

TE RIRI KI ŌRĀKAU - THE BATTLE OF ŌRĀKAU

Shane Te Ruki of Ngāti Unu is a direct descendant of Huihi.

"My tupuna Poupatatē [and] his peer and relation Raureti Te Huia were of a similar age and ilk, they where the left and right-hands to Manga [Rewi Maniapoto] during the battle.... [he] would have been about 14 years-old when he had to go from firing at animals for meals to firing at people trying to take their lands."

Huihi recalled being in Ōrākau Pā with his wife, Hariata Parekura Tamihana, who with the other women helped measure out powder and cut slugs of lead for the muzzle-loading guns.

His rifle was taken by a Pākehā in the Taranaki war. He states that when it came time to escape, his wife outstripped him, "carrying blankets on her back and a string of pannikins around her waist".

"I could hear the bullets of the Pākehās whistling past my ears as they discharged their guns into the scrub behind us. When we reached the Pūniu stream, we were so thirsty we put down our heads and drank like horses".

Te Ruki says, "The break away from Ōrākau in the decade after the war the was complete disruption. [Some were] presumed to have died and others [were] presumed to have survived, everyone was displaced and all over the place".

Hariata Parekura Tamihana, wife of Poupatatē Huihi, was presumed dead but in fact survived.

She went on to live to a grand old age, most of which was spent separated from Poupatatē as she returned to her mother's people in the Hauraki.

In her twilight years, she returned to live with Poupatatē at Kakepuku before passing.

James Cowan wrote in the Otago Daily Times in 1931, "Te Huia Raureti and Poupatatē...the white-beard heroes, now about 90 years of age, were both members of the bodyguard of devoted warriors who safeguarded their chief, Rewl Maniapoto, on the retreat through the swamp of death when the defenders of Ōrākau Pā abandoned their entrenchments on the last day of the siege.

"The Ngāti Maniapoto, by the way, have no special dirges (songs) for Ōrākau. Te Huia explained...'We did not lose any of our important chiefs, there were only a few of our tribe in Ōrākau, hence it was not necessary to make lamentation over it.'”

A 1930 article in the Evening Star describes "Poupatatē Huihi, a half-caste, now very close on ninety years old. He is the son of a roving Pākehā who settled as a trader on the Waipā...Poupatatē is now quite blind. He must have been a splendid figure of a fighting man in his youth; he was still big and broad-shouldered and straight-backed when one saw him last."

After the battle of Ōrākau, Huihi wrote to Sir Māui Pōmare who was the MP representing the Western Māori electorate, now Te Tai Hauāuru, for a war pension.

Vincent O'Malley notes in his book The Great War for New Zealand that, "Poupatatē asked the government for the 'desires of the people in regard to grants made to survivors of Ōrākau Pā', he asked that now the Great War was over, he might receive such a grant. Pōmare referred the matter to the Defence Minister, who advised that he could find no reference to any such undertaking.

"Given there were only six surviving veterans by 1914, any grants would likely have been a matter of a few hundred pounds per annum at most. While happy to celebrate Ōrākau, the government was not interested in extending practical assistance of this kind to its survivors- though military pensions were paid to Pākehā veterans."

Huihi died at his home in Te Kōpua near Te Awamutu at the age of 94.

KĪNGITANGA

Huihi was a great supporter of the Kīnigitanga and to King Tāwhiao, who he was a personal messenger for.

"He would hear word from the king and would drop what...he was doing, his fork would still be on the plate...abandon his meal and take every measure at hand to get to his king as soon as possible, taking canoe, taking horses, running, whatever it took to get to his king," says Te Ruki.

Huihi would ensure that eleven canoes of goods including vegetables, fruit, meat and bread and all sorts were sent to King Tāwhiao every year according to Te Ruki.

The canoes had "one man at the front of the canoe another man at the back with the goods piled up to such a height there was only room for each man to see each head," he says.

"He would carry the different messages of the king to rangatira of the nation before the war broke out. Prior to this, his name was Tāmati or Thomas Hughes. He was named Poupatatē pou o te rangi Huihi by King Tāwhiao as a measure of his dual whakapapa status to both Māori and Pākehā and shorted to Poupatatē."

I A IA E RIRIKI ANA - EARLY YEARS

Poupatatē was raised by his grandfather Te Taiapa, ariki or high chief of Ngāti Makohori, along with his brother Tuapōkai. Their mother, Tautapa, married their Pākehā father James William Hughes, who left her a widow after committing suicide.

As a young man Poupatatē was one of the kīore or scouts of the tribe whose job was to scout the tribal boundaries of Ngāti Maniapoto.

"He and his brother...would walk the tracks from Kakepuku to Te Tapararoa, and even further sometimes to Tīhoe and to Taupō then turn around and come back. Their job as very young men, 13 or 14, was to traverse backwards and forwards those tribal boundaries and pass word onto each of the kāinga that they came to- 'we saw so-and-so, we saw such and such fishing'- which is a traditional role in the tribe." says Te Ruki.

His younger brother Tuapōkai was sent to Miringa Te Kakara, a place where tohunga taught the sons of rangatira their people's knowledge of history, genealogy and religious practices "which left Poupatatē with his grandfather and later he joined Tuapōkai at Miringa Te Kakara too."

"We know he graduated as tohunga...and his knowledge on whakapapa was outstanding" says Te Ruki.