This article was first published on RNZ.

Ōtautahi writer Tina Makereti was just two when her parents split up, and lived exclusively in her father’s Pākehā world until reconnecting with her Māori whānau at 16.

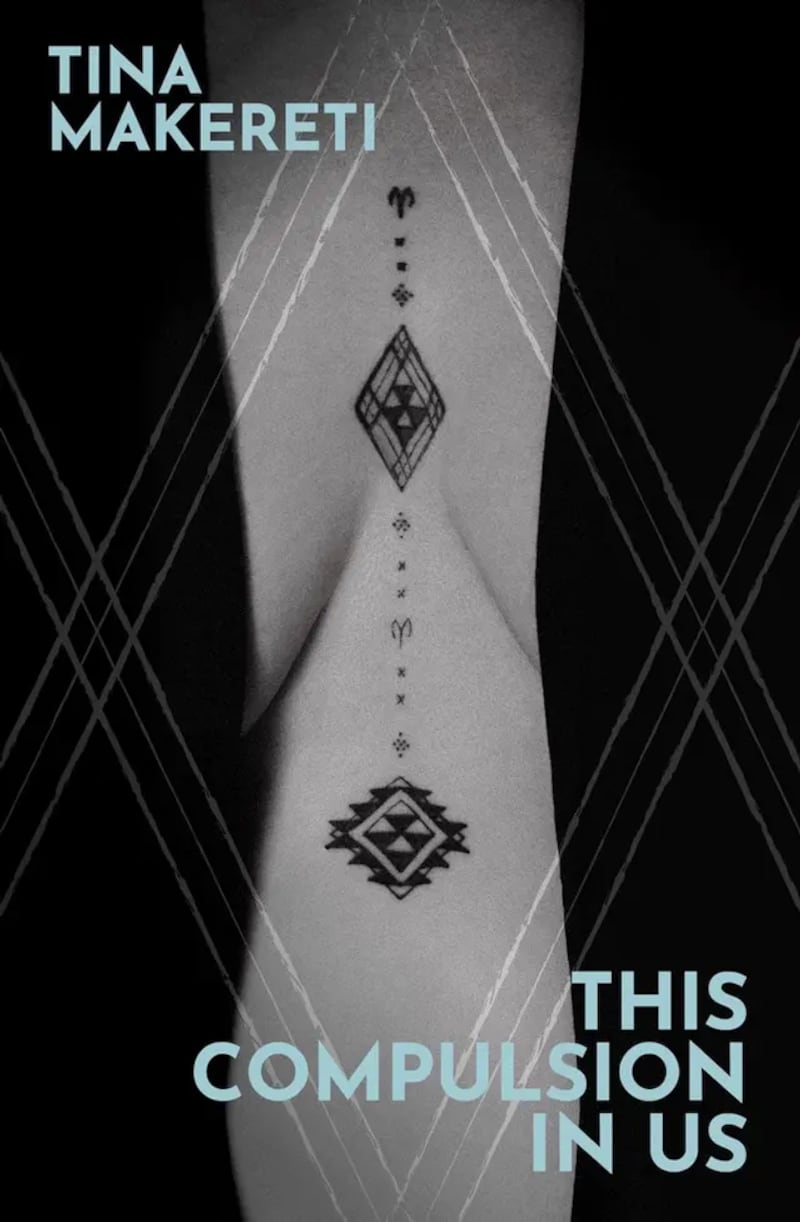

In her new essay collection The Compulsion In Us, Makereti reflects on cultural disconnection, the search for identity and the “wake-up call” she received from a breast cancer diagnosis.

“Cancer said to me ‘Just stop’. I was working too hard, I was burning out all the time. I had taken responsibility for a whole lot of stuff that wasn’t my responsibility, which is so easy for us to do as Māori women… I think that’s basically what we always do.”

Cultural dispossession affects many Māori, but it was especially “extreme” for the young Makereti (Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Rangatahi-Matakore, Pākehā).

During a transient childhood in which she and her sister often slept on a mattress in their dad’s station wagon, he moved them frequently around the North Island and didn’t really speak about their mother’s family.

Years later, Makereti’s father admitted to her that their near-constant movement was partly a way for him to avoid them.

“I laugh about it now, but it’s not funny. We’d spend a lot of time just moving.”

During her “extremely lonely, extremely painful” childhood, Makereti became a watchful and observant person with some of her father’s disrespect for authority - “which sounds like maybe a bad thing, but it was a really good thing”.

As a funny and intelligent man, she believes he could have made so much more of his life if alcoholism and mental health struggles hadn’t been in the way.

“He had deep prejudice, he was full of rage. He didn’t know how to manage his emotions… I could never figure out whether he was just making a choice to be that way. I could see him sometimes trying and then sometimes just choosing to give up. It’s a sad story.”

For a long time, Makereti had as little to do with her dad as possible, so to her, it was interesting to notice her own writing about him in The Compulsion In Us has a “quite affectionate” tone.

“Writing the book actually taught me to love him again and to understand him better. Well, if not to understand him, then to just… have aroha.”

In Makereti’s own family, the fall-out from social dysfunction and cultural disconnection shows up as physical and mental illness, she says.

“I watch my children go through these things. I watch my sister go through these things. I’ve been through these things myself.”

Although it’s “odd for a Māori person”, she has found comfort in the world of academia as a place to intellectualise, think and write, and now teaches creative writing at Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters.

To connect with other people’s humanity from her heart, rather than her mind, Makereti writes books - next a collection of “joyfully dark” short stories.

She says that in New Zealand’s current political divide - which is “deeply, deeply painful” for many Māori - storytelling is more essential than ever.

“Our creative work has become more important to us in this current situation.”

- RNZ