This article was first published by Stuff.

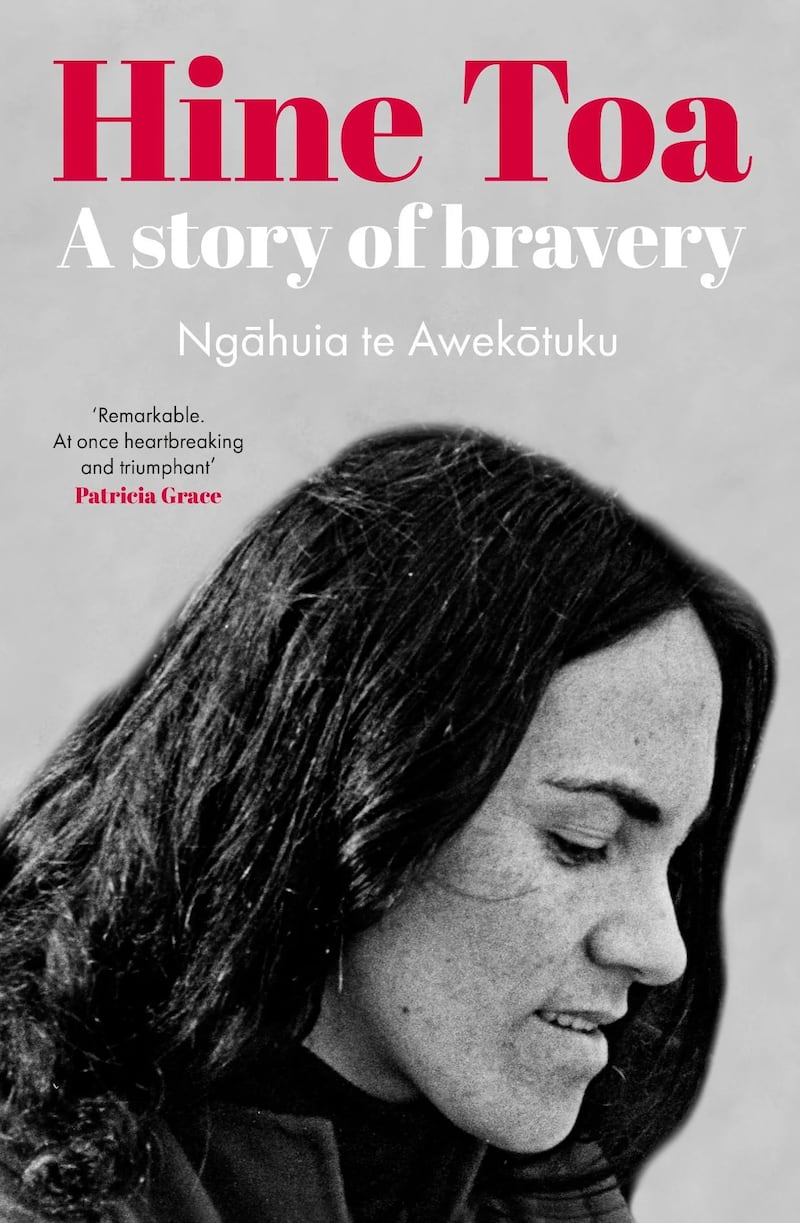

Ngāhuia te Awekōtuku is the winner of the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards General Non-Fiction Award for her memoir, Hine Toa: A story of bravery, published by HarperCollins Aotearoa NZ. In this extract from her memoir, te Awekōtuku shares a treasured childhood memory. Hine Toa is available now, RRP$39.99.

My happy place

Harakeke

My kuia did her weaving in the big shed; it was her workplace. Constructed from recycled timber, it was patched in fading maroon, black enamel and a muddy greyish-green. Large protruding nails hooked sacking, coiled rope, empty containers and assorted hand tools. Two massive panes of glass, purloined from a hotel demolition, lifted shy curving eyebrows to a corrugated-tin roof. The door, a single narrow slab on stout iron hinges, was only closed at night.

Standing high on sturdy piles, the building seemed bathed in light. It was close to the riverbank and faced north-east. But despite the nearness of the stream and the boiling springs, and often the noisy winter rain, the air was never damp, always warm and dry, in my kuia’s workplace.

And there were no tables, not one – eating and drinking happened outside the shed; nothing was consumed around the fibre. Another rule was clean hands; they had to be spotless. Everything was done on the floor, the work surface where my kuia would squat and stretch, often using her feet or her toes to straighten a seam, flatten a mat or secure a skein.

I’d sing my way past the garden, loud so she knew it was me. ‘Kui!’ I’d call out, pausing at the door and shaking my shoes off. ‘What did you make today?’

Facing the window, sitting with her legs crossed under her big long skirt, she’d look up and rest the object on her knees. ‘Another potato kit,’ she might reply. ‘Nothing fancy right now – everyone wants potato kits!’

I’d hunker down next to her, reaching for cut green scraps and looking around. Hanks of plant material lined the walls: some were pale white kiekie in precisely counted strips, others were knotted strands of rich yellow pīngao grass. There were bound clusters of maize – red, orange, purple – to be grown or exchanged, and two Cook Island fans, their brightness dimming with age. A mesh onion bag lined with newspaper contained duck feathers, and another carried pheasant feathers; they hung from nails near the door, with thoroughly washed flourbags of chicken feathers.

A variety of hats mingled with lots of different woven kete, patterned beautifully but mostly damaged beyond repair. Some of these retired baskets were stuffed with materials that I never touched but often wondered about.

A long shelf made of old nail boxes ran along the wall beneath the window, with tins and jars of tools, dried flowers, shells and pencils, which I liked to fossick in, seeking out little treasures. Old rourou or square food baskets, which I’d help scrape clean, carried mussel shells and scraps of pāua; these were fun to play with in the sun, as I marvelled at their glittery rainbow hues.

Overhead, lines of knotted flax crisscrossed just below the ceiling. There were piupiu in different phases of making: some bundled strands of worked and greening flax about to curl; others plaited together and patterned, ready for the dyeing process; and always two complete and finished kilts spread like fans below the rafters, stark black and white, ready for collection. Skeins of fibre in various stages of colour were suspended, drying. Fixed first with a bath of kānuka branches, most were dyed traditional matt black, from paru, the gleaming mud found in secret parts of the Maketū swamp, near the whānau’s old fishing hut on the coast. That is how I remember it. The paru was gathered and then stored near the bath in the reeking old copper with its big lid. This is why it was tapu: it was rare and special, and it could ‘hear’ things. If you talked dirty or had mean thoughts around it, the blackness would turn away, and the dye would not take. And my kuia always knew, and questioned us.

Other colours gleamed brightly: mint-green to emerald made from soaking fibre in green apple paper water for hours; the deep purple to light violet of purple fruit papers treated the same way. One of my jobs was to go to the Hindu fruiterers and collect this bounty.

Bhavatu B. David’s shop displayed the produce at the front, shallow wooden boxes crammed with glossy apples, juicy pears and suckable oranges. Mr David polished them with a special rag. Bananas hung yellow from hooks knotted in gardening twine. Vegetables sat along the walls.

Sometimes my kuia would also call in with a woven purse or trinket that she gave to the fruiterer’s wife, exotic in her tinkling glass bangles and silky whispering sari. She hovered quietly at the back of the shop, with the unpacked produce and sometimes a sleeping baby. The child was nesting blissful in feather-soft blankets under a foggy mantle of smells, fruity and dusty and foreign. Indian. Like this young mother with a ruby twinkling in the side of her nose.

She didn’t have as many English words as my kuia, but they understood each other perfectly.

‘Thank you, Mrs Luxmi. Māu tēnei mea iti, little thing for you.’

Thoughtful nodding, a shy response of shining teeth.

‘Lovely good, thanks.’

‘Āe, lovely good.’ My kuia began to glitter like the ruby, and home we’d go with an onion bag stuffed with pear and apple papers to turn into dye.

Red was a rare and coveted hue. My kuia tried various sources before she came upon the pinkish covers of the Auckland Weekly News magazine. Rendered down in a kerosene tin over a fire, these made an acceptable shade – but it took dozens of them, so red artfully appeared only on special purses like dainty decorative kete, not all-purpose everyday ones. Watching this happen was like watching magic, the red deepening until it looked like Koro’s special wine as I stirred up the sludge with a cracked wooden spoon. I prodded and fiddled until Kuia took it off me and checked the colour. ‘Ātaahua,’ she sighed, dipping in a whisp of raw fibre to test it. ‘Ātaahua.’

Underneath my bare feet in the shed – we always removed footwear in all our dwellings – was a mix of flooring just like inside the house. Whāriki or traditional plaited mats, lumpy homemade rag rugs, coal sacks spongy to tread on, and carpet offcuts covered a lot of smooth bare wood.

Newly scraped, flawlessly pale fibre sometimes floated, whitening, on the incoming air. These suspended threads were the beginnings of a cloak.

I loved the feel of the bundles of colourful fibre touching me as I walked beneath them, and the slight give of the coal sacks under my soles, and, always, the fragrance of the flax all around. I loved being in my kuia’s shed. And sometimes she would let me help, and I had a special job: we called it soaping the feathers.

‘That box –’ she’d indicate with her chin, while her hands twisted strands of fibre ‘– the fawny ones over there. And the other box with the dark ones.’

I grabbed the boxes, side by side, and opened them up, holding down a sneeze.

My kuia laughed then, smiling at me. ‘Hoatu ki waho. Go outside, Hui, and sneeze in the garden.’

So I did. Sneezing would set the feathers flying, and it was a waste of time picking them up and sorting them again by colour and size, all fluffy in their brown cardboard shoeboxes.

‘Is your soap ready?’

‘Āe, Kui, it’s good …’ I proudly showed her my mussel shell.

She pressed its contents, approving the moistened yellow lump of Sunlight soap that I’d prepared. ‘Pai ana tēnā; yes, that will do.’ She continued her work with a caring eye on mine.

I picked up three feathers: one medium, two smallish. Once they had been on a living kiwi who ran about cheeping her sweet happy song among the ferns in the middle of the night, probing for kai with her long skinny beak. Now she was dead, just feathers, and my kuia was bringing her back to life, weaving them into a cloak.

She noticed my attention wandering. ‘Kare, how many have you done?’

I’d finished my second little twist of feathers; with the lightest smear of soap, I’d twirled the downy fibres on the quills, binding the three together. I’d placed them carefully on the lid of the box, side by side – only two twists of three feathers. They were ready to be plaited in to the fabric of a new garment or an evening purse. ‘Only two so far …’

I gulped, knowing I should’ve made more, but instead Huia, a cheerful wee bird with her own long skinny beak and very handsome plumage, had been playing in the ferns with the kiwi.

The old lady gathered me into her strong arms, holding me close against her scent of crumpled woolly cardigan and cool flax leaves. ‘Ah, Huia, you were dreaming stories again, weren’t you?’

- Stuff