Canada — Canada’s history is littered with atrocities committed at residential schools, but now, one former site is being reimagined.

The grounds of the former Shingwauk Indian Residential School in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, will soon be home to Makwa Waakaa’igan, an Indigenous-led, 37,000-square-foot national centre for cultural excellence, education, and healing.

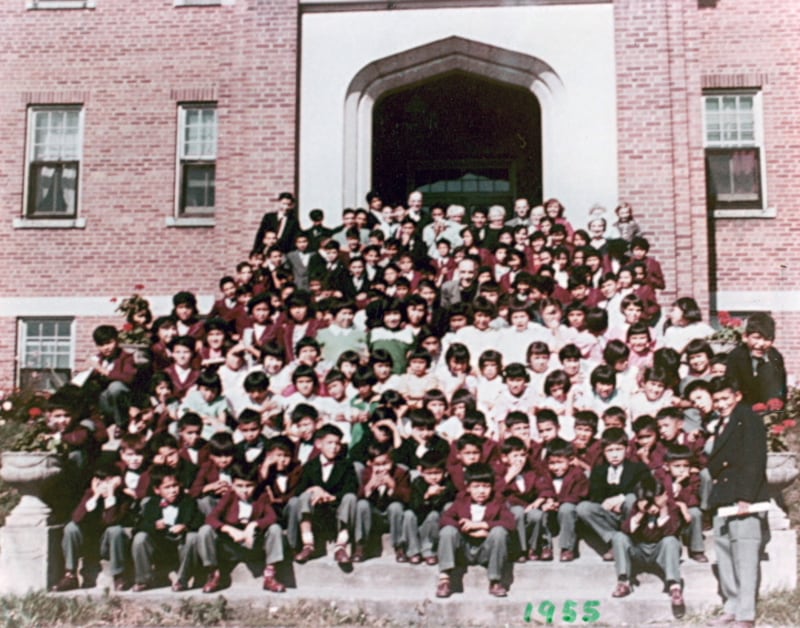

An official groundbreaking ceremony took place on the grounds beside Algoma University, where the Shingwauk school operated from 1873 to 1970.

During that time, children from 184 First Nations communities across Canada were taken from their families, language, and culture.

Makwa Waakaa’igan, which means “Bear’s Den” in Anishinaabemowin, aims to turn that legacy of loss into a future of restoration.

“Makwa Waakaa’igan is a place of tradition, learning, wisdom—all the elements that reflect the healing journey of former students,” said Shirley Horn of the Missanabie Cree First Nation, and a member of the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association.

Horn, who survived the residential school system herself, later became Algoma University’s first chancellor.

She explained that the bear, Makwa in Anishinaabe teachings, is revered as a medicine carrier, healer, and guardian.

Before construction began, elders led a ceremony that included tobacco and traditional medicines as offerings. Prayers were also offered to acknowledge the Creator and the land.

Survivors at the centre of the vision

Makwa Waakaa’igan is deeply shaped by the voices of survivors, who have guided its design and its purpose.

Joel Syrette, President of Makwa Waakaa’igan, says, “We understand that everything in the natural world is in the realm of the living, and has a spirit.

“And even things in the Earth when we dig down, that’s somebody who lives there, beings who live there.

“And any time we disturb anything in that natural order, those offerings are made to ask to move forward in the best of ways, because what we’re taught by our elders is that the only thing, really, that we leave behind is our footprints.

The $5-million federal investment announced in 2024 will ensure the project remains rooted in its vision and governance led by survivors.

Member of the Niiyaagaaniid Anishinaabe Initiatives, Martin Bayer says, “We had to ask the Creator for forgiveness for having disturbed the land as we start with more construction. It’s also good that we’re announcing the next phase of the construction of the Makwa Waakaa’igan.”

A space for memory, learning, and healing

Makwa Waakaa’igan will include classrooms, cultural learning spaces, ceremonial halls, and a community gathering area. At its heart will be a groundbreaking archival centre, dedicated to safeguarding the records of more than 87 First Nations communities whose children attended the Shingwauk school.

Syrette says, “There will be community gathering spaces, there will be cultural learning spaces, and, as well, there will be an archival center that will be the first of its kind to really care for the archival collection of more than 87 communities that had students and children attend the school, many of whom never made it home.”

Horn says, “And also the cradle of learning and everything that we can share with future generations, but also with many other countries and the world. I’m very, very proud of that and look forward to continuing the work with Algoma University. I certainly value the connection that we have made together in the spirit of Truth & Reconciliation.”

Makwa Waakaa’igan is expected to be completed by November 2026.

A site of historic pain and future promise

The Shingwauk Indian Residential School, designated a National Historic Site in 2021, operated for nearly a century. More than a thousand First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children passed through its doors—many never returning home. The institution enforced assimilation through harsh discipline, forced labour, cultural erasure, and emotional and physical abuse.

Today, the school’s last remaining stone dormitory houses Algoma University and the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre, where survivors work to protect and interpret the records of their classmates.

Now, just metres away, Makwa Waakaa’igan rises as a survivor-led response to that painful history. It represents not just remembrance, but resurgence—offering a place for Indigenous-centred education, land-based learning, ceremony, and cross-cultural dialogue. It is a vision of Truth and Reconciliation made real.