Fifty years since its establishment, the Waitangi Tribunal remains one of Aotearoa’s most significant - yet contested - institutions. Born out of struggle, it has amplified Māori voices, documented breaches, and reshaped the nation’s understanding of its colonial past.

While the Tribunal has been a safe place for Māori and the Crown to have hard conversations, it has been described as both ‘a compass’ and a ‘toothless taniwha.’

Since the advent of the Coalition Government in 2023, the Tribunal has once again become a political football. It is facing accusations of “activism” and scrutiny over appointments, with calls for a full review of its powers.

Te Rōpū Whakamana i te Tiriti o Waitangi, the Waitangi Tribunal, turns 50 this year.

Established under the Treaty of Waitangi Act in 1975, the Tribunal was created to investigate breaches of the Treaty by the Crown.

But as legal academic Professor Jane Kelsey explained to Moana Maniapoto, it wasn’t an act of goodwill, but the result of sustained Māori and international pressure.

“The Tribunal wasn’t a piece of magnanimous decision-making on the part of the Crown,” Kelsey said.

It only became law because of concerted activism on the part of Māori. Even Labour MP Matiu Rata, the Māori Affairs Minister who championed the Tribunal’s creation, faced resistance from his own party.

“They would only agree to if it would only look at potential grievances after the Treaty of Waitangi Act was passed in 1975,” Kelsey said, noting they will have assumed that excluded all the big issues like loss of land.

The legislation was passed just before the 1975 general election and right as the historic Land March arrived in Wellington.

According to Kelsey, the National Party leader and newly elected Prime Minister Robert Muldoon had no intention of setting up the Tribunal at all.

“He was going to have to set up a Human Rights Commission because of UN treaties,” she said. “He was just going to slip it into there.”

A spanner in the works

One of the first major tests of the Tribunal came in the late 1970s with Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei leader Joe Hawke.

Although a permit was required to gather kaimoana, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei continued to fish for hui and tangihanga, asserting they had never surrendered their customary right to do so.

Hawke, who exercised that right, was prosecuted.

“He lodged a claim with the Tribunal, which meant they had to set it up,” Kelsey said.

Though his claim failed on a technicality, it marked a significant moment for Māori.

The Tribunal was underway.

From 1980, under the leadership of Sir Eddie Durie (Rangitāne, Ngāti Kauwhata, Ngāti Raukawa), the Tribunal began to grow in stature and impact.

“Eddie Durie took the Tribunal from where it was with Joe Hawke’s claim in the ballroom of the Intercontinental Hotel back onto the marae,” Kelsey said.

It was a cultural and political turning point. Claimants were not required to swear oaths on the Bible and were able to present evidence in both languages.

Reports from the Manukau, Motunui, and Kaituna inquiries found that there was no cession of sovereignty by those claimants.

In 1985, Parliament expanded the Tribunal’s powers to hear claims dating back to 1840.

Impact and influence

Since its inception, more than 3,370 claims have been lodged, with over 130 inquiries completed.

The Tribunal’s reports have shaped some of the most transformative moments in modern New Zealand history and created the momentum for political change.

Its 1986 report into te reo Māori helped drive the Māori Language Act 1987, the establishment of Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori, and the rise of Māori radio and television.

Yet despite this influence, the Tribunal’s recommendations are not legally binding, which remains a source of ongoing frustration for claimants.

In 2018, the United Nations also expressed concern about successive governments frequently ignoring Tribunal findings.

Ground Zero

Lawyer Māui Solomon (Moriori/Ngāi Tahu), who has acted as counsel in the Wai262 claim and long advocated for the rights of Moriori in Rēkohu (Chatham Islands), shared his frustrations on Te Ao with Moana once treaty negotiations with the Crown were underway.

“Even though there were very clear and strong findings from the Waitangi Tribunal, it was like ground zero with Te Arawhiti (former Office for Māori Crown Relations),” Solomon said.

“We had to re-prove everything from the beginning, even though we had a substantial report in our favour.”

For Solomon, the Tribunal’s power had been in its ability to restore identity.

“I was told at school that Moriori didn’t exist,” he said. “The Tribunal said we were still a distinct and unique people with this peace covenant intact. That meant a huge amount to me.”

Political resistance is nothing new

The Tribunal’s 50th year has not been without controversy.

Appointments to the tribunal are made on the recommendation of the Minister for Māori development. Māori and non-Māori members alike are chosen for their expertise and knowledge of matters likely to come before them.

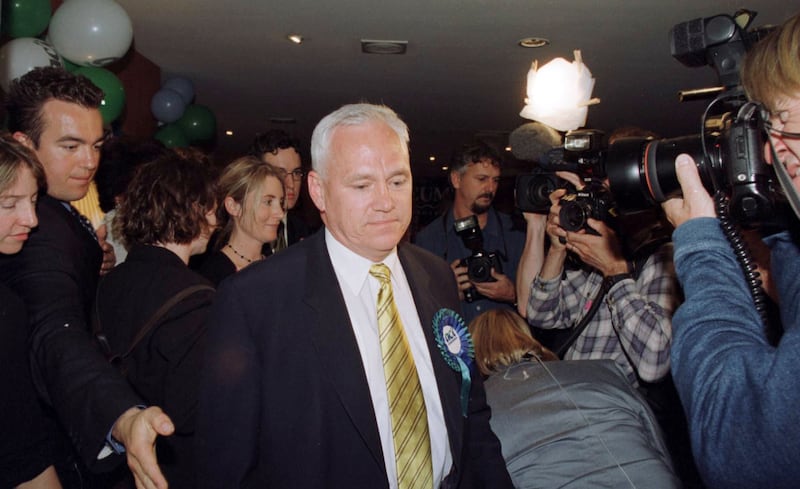

Internationally respected scholar Professor Linda Tuhiwai Smith did not have her warrant renewed while former ACT Party leader Richard Prebble was appointed, but resigned before taking up the role, calling for a review of the Tribunal.

While Prebble declined to be interviewed for Te Ao with Moana, ACT leader David Seymour claimed the Tribunal had gone “well beyond its brief” and become “increasingly activist.”

Lawyer Max Harris disagreed.

“It’s been a bit of a strategy in multiple countries to suggest judges are being activists when they’re really just holding governments to account,” Harris said. “The work the Tribunal has done recently has been very comprehensive and considered, and it’s been in line with its original legislation.”

Kelsey echoed a similar sentiment.

“It is also the only space in which the feet of the Crown can be put to the fire. And when they don’t appear, that speaks volumes for itself.”

A flashpoint in 2024 was the Tribunal’s decision to summon Children’s Minister Karen Chhour.

The Minister refused to appear voluntarily during an urgent inquiry into the Government’s decisions to repeal section 7AA of the Oranga Tamariki Act. Crown Law went to the High Court, successfully arguing the summons was unlawful.

That decision was overruled by Court of Appeal judges who wrote: “It is not clear to us why the constitutional relationship between the Crown and the Tribunal should prevent the Tribunal from asking for information that would, in its view, assist it to carry out the inquiry.”

The Tribunal today

Over five decades, the Tribunal has built an extraordinary archive of mātauranga Māori, oral testimony, scientific evidence, and legal precedent.

Yet the Tribunal remains under pressure externally in a political climate that’s grown increasingly anti-Tiriti.

“Those things that are happening become a part of the claims before the tribunal,” says Jane Kelsey. “The tribunal gets caught also in that space, under pressure to make recommendations to governments that have already predetermined that they’re not going to listen.”

“That means the Tribunal can find - as it has with the Treaty Principles Bill - that the Crown is profoundly in breach of Te Tiriti o Waitangi,” Harris said. “And the Crown can ignore that.”

Looking to the future

There are 2160 claims still active.

The Tribunal is currently undertaking a major constitutional kaupapa inquiry, revisiting foundational questions of kāwanatanga and rangatiratanga – teasing out issues raised in the Urewera, Rohe Pōtae, and Te Paparahi o te Raki inquiries.

The Constitutional inquiry has also returned hearings to marae settings.

But whether the Crown wants to hear its recommendations remains to be seen.

As Aotearoa heads into another election cycle, the future of the Waitangi Tribunal depends on whether the nation sees it as having value.

For Māui Solomon, the Tribunal represents potential and hope.

“I heard a former mayor speak about the Treaty Principles Bill. He called himself a ‘recovering racist’,” he said.

“Through his work with Māori, he came to understand the history and the interaction.

“The Tribunal has a lot to teach both Māori and non-Māori about our shared history.

“We’re not responsible for the actions of our ancestors, but we can acknowledge what happened and build something better. And the Tribunal still has a very important role in that.”

Watch the episode on Te Ao with Moana

Whakaata Māori, Mon 8pm and Māori+